In the preceding centuries, the Byzantine empire had been been weakened by attacks from the Arabs

and later by the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks.

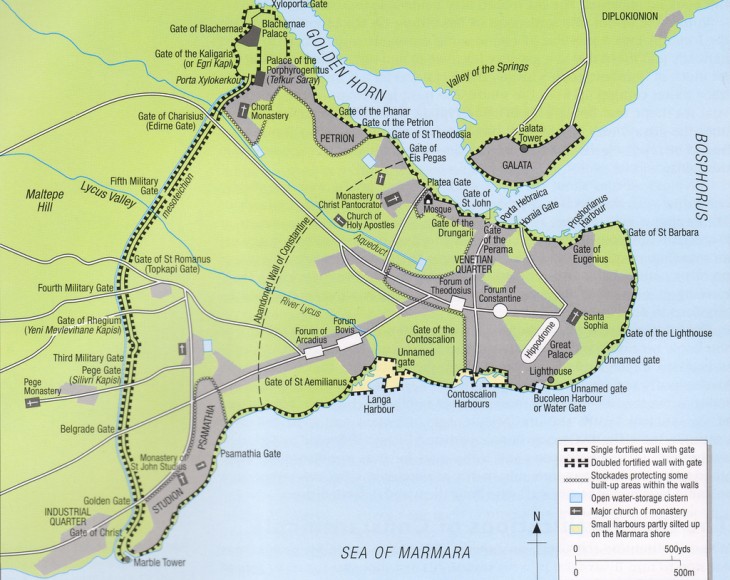

However much of its wealth and power resided in its capital, the city of Constantinople, which was well protected by water and massive walls.

This stronghold had been taken only once, not by muslims but christians, during the Fourth Crusade.

Afterwards it was severely depopulated.

The Ottomans had capitalized on this power shift by carving out an empire in Anatolia and extending it into the Balkans, surrounding the city as early as the 14th century CE.

Still they could not capture the city itself.

Sultan Memhmed set out to change that.

The Turks finished the construction of a pair of fortresses on the eastern Bosporus, squeezing Byzantine naval traffic to and from the Black Sea.

The Byzantines saw the storm gathering and applied for help to the west, but little was coming forth,

as many westerners thought they could do business with the Ottomans as well as with the Byzantines.

The latter built a chain across the Bosporus to stop Turkish ships and reinforced their walls.

In the spring of 1453 CE Mehmed arrived with a force of 50,000 - 80,000 soldiers, 1/10 of them janissaries.

Part of these attacked over the water with a fleet of more than 100 ships of various sizes and purposes.

Inside the city there were probably less than 50,000 civilians and an army of 5,000 Byzantines; 700 Genoese mercenaries;

1,300 other allies and volunteers, including even Turkish mercenaries.

The Ottomans surrounded the city on all sides.

The Byzantines manned only the outer walls, as they lacked numbers to guard everything.

Both parties put their best forces at the Mesoteichion, the middle section of the western wall.

Earlier, the Hungarian engineer Orban had offered to build bombards for the Byzantines, but they lacked money.

So he sold his skills to the Turks instead, constructing some 70 bombards for them.

The largest, the "Basilica", could fire only a few shots per day, yet flung its stones up to a mile.

After a while the barrel started to disintegrate under the strain and it put itself out of action.

All the guns combined fired around 120 shots per day, about 5,000 throughout the entire siege.

They sometimes shattered whole sections of the walls, though did so infrequently.

Most damage was quickly repaired at night with stakes, earth and anything else that could be used.

The defenders had guns too, which were smaller, but their recoil proved harmful to the walls.

So the guns played an important role.

However they did not simply win the battle on their own.

After some weeks, a supply fleet managed to reach the city, bringing supplies and rasing morale.

The Ottomans decided to strengthen their blockade.

They were hampered by the chain in the Bosporus, but ferried some of their ships overland north to the Golden Horn, to block supplies from the Black Sea.

The defenders tried to break the blockade with fire ships; the attempt failed miserably.

In the meanwhile, on land, the Turks mounted several assaults on the walls, to see them all repelled.

Then they switched to a tactic of undermining.

The Byzantines dug countermines and a few grim dark battles were fought underground.

When two Turkish soldiers were captured they were tortured to reveal the location of the remaining tunnels, which were then destroyed.

After nearly two months without a breakthrough and a hesitant relief fleet from Venice finally underway, the Ottomans tried diplomacy.

The Byzantine emperor agreed with some concessions, though was unwilling to give up the city itself.

Opposed by his senior councellors but supported by the juniors, Mehmed ordered an all-out assault.

After a lengthy preparation the attack started at midnight.

Some irregulars and then Anatolians managed to break into a weakened section in the northwest, but were cut down by the determined defenders.

They were followed by a wave of fresh Janissaries, who raised a flag to rally the attackers and furiously attacked the now exhausted Byzantines.

When the Genoese commander Giustiniani was shot down there was confusion; many thought that the lines had been broken.

The Turks noticed and pushed with all their might, swamping the area.

They broke through at the gap and also at the nearby small Kerkoporta gate.

Soon afterwards the resistance crumbled.

Some defenders tried to rescue their families; others aimed for an escape by ship; some committed suicide.

The city was looted for three days, as was customary.

Many prisoners were sold as slaves.

The Byzantines suffered several thousand casualties; the Turks probably several tens of thousands.

The Hagia Sophia was converted to a mosque and Mehmed made the city his new capital.

The Ottomans went on to extend their empire northwest until it reached Vienna in 1529 CE.

In the meanwhile the emphasis of European trade shifted westward, ultimately leading to the European discovery of America and trade routes around Africa.

War Matrix - Fall of Constantinople

Late Middle Age 1300 CE - 1480 CE, Wars and campaigns